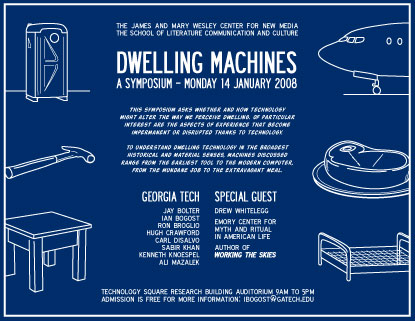

This past Monday the School of Literature Communication and Culture and the Wesley Center for New Media at Georgia Tech hosted a symposium I organized called Dwelling Machines. Here’s the description, too small to read in the event poster above.

This symposium asks whether and how technology

might alter the way we perceive dwelling. Of particular

interest are the aspects of experience that become

impermanent or disrupted thanks to technology.

to understand dwelling technology in the broadest

historical and material senses, machines discussed

range from the earliest tool to the modern computer,

from the mundane job to the extravagant meal.

A number of my Georgia Tech colleagues presented, as well as a special guest from Emory, Drew Whitelegg, who wrote my favorite book on flight attendants, Working the Skies.

We tried to record the event and I’m hopeful we’ll be able to turn it into a podcast soon. In the meantime, I thought I’d post the introduction I gave to the event. There are many connections to my previous and future work here, even if it seems a bit out of left field.

“A house is a machine for living in. Baths, sun, hot water, cold water, warmth at will, conservation of food, hygiene, beauty in the sense of good proportion.”

â?? 1923, Le Corbusier

When Le Corbusier said that houses are “machines for dwelling,” he meant something very different from what we have in store for today.

Like so many things, Le Corbusier imagined a home as a precisely functioning machine with parts designed, arranged, and adjusted for maximum economy.

Most famously, these ideas took form in modular building construction and design for efficiency. The purported purpose of these designs was to improve quality of life for the masses, a concept common in many of modernism’s attempts to grapple with the changing landscape of urbanism and industrialism. In Le Corbusier’s case, architecture was a cornerstone, as it were, of a broader social utopianism. In his famous Unité d’Habitation, individual apartments were slotted into a rectilinear grid, “like bottles into a wine rack,” to use the architect’s own words.

I am not an architect or a scholar of architecture, so apart from Le Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine, my favorite example of urban utopianism comes not from a planner but an entertainer.

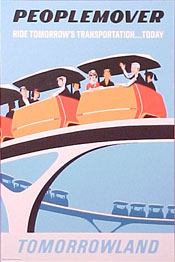

Ironically, Walt Disney’s motivation for designing the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow involved many of the same concerns about disorganization and crime as earlier modernist fantasylands. Less theme park than experimental city, EPCOT was supposed to be a residence for park employees, a commercial district, a convention center, and of course an ongoing and evolving world’s fair where new machines might make their debut. The city was to feature a radial urban design, with regional transit provided by monorail, and local transit by the People Mover. The latter was installed at Disneyland in 1967 and bears considerable resemblance to future-visions of urban transit from the 1930s.

Ironically, Walt Disney’s motivation for designing the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow involved many of the same concerns about disorganization and crime as earlier modernist fantasylands. Less theme park than experimental city, EPCOT was supposed to be a residence for park employees, a commercial district, a convention center, and of course an ongoing and evolving world’s fair where new machines might make their debut. The city was to feature a radial urban design, with regional transit provided by monorail, and local transit by the People Mover. The latter was installed at Disneyland in 1967 and bears considerable resemblance to future-visions of urban transit from the 1930s.

Epcot was never built, of course, at least not in the way Walt Disney had intended. But the idea of the theme park as experimental city is different both from both Le Corbusier’s vision of wholesale redevelopment and Baudrillard’s take on Disney as pure hyperreality. Inconceivable to both is the idea that people might negotiate with their dwelling machines, one pushing and pulling on the other through disruption more than acquiescence.

Oddly, the “Magical Express” buses that haul Disney World goers from the Orlando International Airport to their themed hotels play a segment of the 1966 film in which Disney explains his vision for EPCOT. Some of this potential can be seen in what little residue of the original EPCOT concept actually remains. Even though Disney World makes use of monorails for guest transit rather than just as an attraction as Disneyland, the bus takes the place of the monorail at the property’s newer theme parks and hotels. This is hardly a surprise, given the fact that the recently constructed Las Vegas monorail reportedly cost $142 million per mile, or almost double the planned per mile costs of the latest sighting of the mythical 2nd Avenue Subway in New York City. But the twilight of the monorail is something of a loss; for many Americans vacationing from cities with little or no functional public transit, the trains are the a kind of Transportland, a fantasy of what public conveyance might feel like in a different world â?? different for them anyway.

It’s always easy to look back on utopianisms with a knowing sneer, especially those that led to so many structures crafted of poured concrete or poured consumerism, or in Epcot’s case, both.

But this is not reason enough to dismiss the potential value of a dwelling machines as a theoretical compass.

Le Corbusier’s “machines for dwelling” fuel themselves from rationalism, a logic where accident has no place, where cold machines simplify human life without concern for its humanity. Disney’s experimental city replaces this rationalism with a warm, but centralized human hand that guides and controls the use of machines. As is the case for all utopian visions, nothing is quite so simple.

There are important unexplored notions of impermanence implicit in Walt Disney’s concept of the experimental theme park city. Unlike his namesake company’s infamous new urbanist planned community Celebration Florida, and unlike Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse, this was to be a place one visits and then leaves, experiencing something that might disrupt a visitor’s idea of home as much as it reinforces his experience of fantasy.

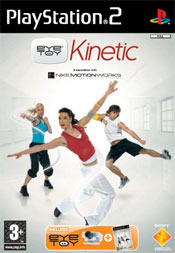

Of particular interest to me and to the Wesley Center for New Media, a co-sponsor of this event, is the relationship between dwelling and the particular machines called computers. The one that piqued my interest in this topic in the first place has to do with videogames, specifically so-called exergames, or games that people play for exercise (I wrote about these in my recent book Persuasive Games). Advertisements and media images of these devices typically depict them in an empty space, a white room like a gallery where no activity takes place. These environments go beyond even the idealized spaces of home furnishings catalogs. Material factors like dens built around a place to put down a beer, as well as limited LCD and plasma screen viewing angles make moving around in front of these games difficult. But their very insertion into such an environment also throws assumptions about couches and coffee tables into relief through disruption. Contrary to the more frequent utopian vision of easy fitness at home that surrounds exergames, they show us how little freedom of movement we really have in the living room.

Of particular interest to me and to the Wesley Center for New Media, a co-sponsor of this event, is the relationship between dwelling and the particular machines called computers. The one that piqued my interest in this topic in the first place has to do with videogames, specifically so-called exergames, or games that people play for exercise (I wrote about these in my recent book Persuasive Games). Advertisements and media images of these devices typically depict them in an empty space, a white room like a gallery where no activity takes place. These environments go beyond even the idealized spaces of home furnishings catalogs. Material factors like dens built around a place to put down a beer, as well as limited LCD and plasma screen viewing angles make moving around in front of these games difficult. But their very insertion into such an environment also throws assumptions about couches and coffee tables into relief through disruption. Contrary to the more frequent utopian vision of easy fitness at home that surrounds exergames, they show us how little freedom of movement we really have in the living room.

A part of the question raised by the title “Dwelling Machines” is how we might decouple the machine from its mixed history with utopia. One way to do this is to imagine the machine as a much more mundane object. If we treat “machine” as a general term for a material situation, we start to see them everywhere. The question then shifts: how do everyday objects like hammers, airplanes, and steaks relate to our experience of dwelling? How do they disrupt that experience and suggest new directions for it? How do we manipulate them as media rather than they us as slaves? These are among the questions we will pose to one another today.

Comments

Ian Bogost

Por Favor Manténgase Alejado de las Puertas

Fandom and Detritus