I often worry about the consequences of what Siva Vaidhyanathan calls Googlization, the way Google is changing and disrupting the creation and dissemination of ideas. I’ve resisted using Google services like Gmail and Google Docs, despite their popularity and, in some cases, their convenience. I’ve mostly been disinterested in allowing Google to mine and profit from my information, but this week another, new concern reared its head.

Early in the morning of June 10, my web host was compromised, and a script was run across the entire server on which my site is hosted. The exploit installed hidden links, via iframes and javascript document.write commands, which redirected invisibly to malware sites. This is a relatively common way for malware attacks to begin. When users mistakenly or unknowingly navigate to a web page with exploits, new processes might be started on the host computer, which could later be used as trojan horses to distribute additional malware or viruses, or which could steal sensitive information like passwords via keystroke logging.

Google attempts to protect people from malware by using their indexing system to detect malware on sites, and to mark them as potentially dangerous. You can see this in Google search results marked “This site may harm your computer.”

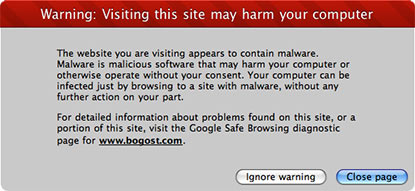

All the popular web browsers, including Firefox, Safari, and Chrome, rely on Google’s reports of unsafe sites in its internal browsing system. When a user tries to visit such a site, these browsers display a warning message like the one below.

Because my site is popular enough to be frequently indexed by Google, their system had already flagged the site as a malware distributor before I was even aware that the server had been compromised. This was inconvenient to say the least, because removing the warning requires one to notify Google that the site has been cleaned, in order that Google can initiate a new check of its contents.

Take close note of this process: one must sign up for a Google account in order to be able to rescue one’s site from having been marked as unsafe by Google.

Unknown to me, Twitter also uses the Google unsafe warning as a way to flag accounts as spammers or malware distributors. Before I’d even completed restoring the hacked files on my site, Twitter had suspended my account, because my profile links to this site.

Google reindexed and cleared my site quickly. When I contacted Twitter, they sent the following “helpful” advice:

If you feel you’ve been suspended in error, please reply to this email with a short explanation if you haven’t already, and don’t forget to include your user name. We will do our best to get back to you within 30 days.

My site is more important than my Twitter account, but given the fact that I was speaking at a conference yesterday at which Twitter was in common use, not to mention the fact that my annual performance of Twittering Rocks is only days away, it is inconvenient to have my account disabled. It’s also mildly embarrassing, because the big red notice on my account page suggests that I am a spammer.

Thanks go to the kind souls who tried to advocate for me on Twitter, an act that seems to have done no good. Perhaps my Twitter followers (who seem to be disappearing slowly for obvious reasons) might consider Tweeting this post as a way of spurring discussion about the policy. Except, as Clint Hocking points out in a comment below, you can’t link to this site from Twitter, since it seems still to believe that this site is dangerous; URL shortening works as a workaround. (Update: Twitter restored my account in four days rather than thirty.)

The particular sort of cascading failure sheds light on an often unseen power Google holds, one that extends far beyond privacy and personal information. Web browsers and services like Twitter trust Google’s reports of online danger implicitly. Yet, Google’s system makes no distinction between people who have malsites and people who get hacked and then fix their sites. Neither Google nor Twitter notified me at all, despite the fact that both have my email address via my respective accounts at those services, nor did they give me any fair warning to remedy the problem before they took action. Instead, they just treated me like a cybercriminal.

As Google offers more and more business to business services like malware detection, and more and more third-parties use those services, this particular type of Googlization can only grow in impact. And the worst part of it is, you can’t do anything about it. One can choose not to maintain a Google account or to use Google services, but one can’t prevent Google from maintaining you.

Comments

Clint

We can’t tweet this post… it’s blocked. Else I would.

jeremy

Wow, the twitter bit is a new trick… That hasn’t happened to me yet, but i’m 2x through the google olympics. However, i tend not to blame them. They just use data from the malware project of harvard and utoronto. I know everyone is acting in good faith and such, but this is a pita to get straightened out. my last hack was apparently because of the blog software that i use… likely the same with yours, it was a common exploit… If i’d been paying attention to my analytics instead of other things, i’ve have caught it faster, but it happened when i was pretty distracted… time of year… In any case.. it would be good to get warnings before we get dropped and escalated…

Ian Bogost

Clint, you’re right, Twitter is apparently preventing links to bogost.com since they still think the site is harmful. URL shortening the link with a service like tinyurl or bit.ly seems to get around the problem.

Trevor

Looks like we need to finally add the third leg to life’s Stool* of Inevitability:

1) Death

2) Taxes

3) Google

*sorry for the scat pun, but (unfortunately) it works…

Andrew Petersen

Ian,

I found this post through… Twitter! I appreciate this post, as I often wonder myself about our reliance on the Google.

However, I don’t think it’s completely unreasonable that Google automatically assumed your site was dangerous. I DO think it’s unreasonable that they did not contact you — an automated e-mail seems trivial. I assume that Google, as it indexes the entire WWW, encounters so much spam and malware that the percentage of said WWW == spam would make any web enthusiast cry. Thus, they have to assume dangerous rather than mistaken. Just because your site was infected against your will does not make it any less dangerous!

This assumes that google has the right to police the pages it indexes. Really… they do. Google is a service, with technically no ties or responsibilities reigning them in.

I think it’s important to remember that Google isn’t like the water company or other utilities that are government regulated to benefit us (if they actually do that is debatable, of course). They just happen to be best at what they do right now.

Thanks again for the post!

zota

Once Google is the de facto worldwide arbiter of legitimate information — which they now absolutely are — they are far more powerful that the water company. They can effectively tell the water company that you are illegitimate and you do not deserve a connection. (This really isn’t much of an exaggeration.)

Given their absolute power, it is far past time to hold Google accountable force them to offer some semblance of responsiveness to the public they now hold at their mercy.

Throwing out an idea — I can call the water company and ask why my water is shut off, maybe get it turned back on. How about we can contact a human being at Google when they pull crap like this?

Gerald

Keep it in perspective guys, if you’ve had your water turned off before (through no fault of your own) you know how difficult it can be to get it turned back on. And more importantly, you know how much more painful it is to have no water.

It sounds to me like Google reindexed your site pretty quickly and that Twitter is the bigger culprit. Is that right?

Not to defend Google but can they do differently than they did? Your site had malware, they flagged it, they reindexed once you cleaned. What other process would you propose?

Ian Bogost

Gerald: This wasn’t meant to be a complaint post wherein I hoped to blame Google or Twitter or anyone else for disrupting my service. Rather, through my misfortune it was meant to spur thought and discussion about some of the implications of Google serving as an arbiter of intermediary trust for other services (including Twitter). I do have my own opinions on the matter, to be sure, but I think I’ve been pretty measured in expressing them above.

I will add this: when the water works shuts down someone’s service, the mail service doesn’t shut down the line after having learned of this fact invisibly, nor does it post an erroneous fraud notice on one’s mailbox.

barbara

Thank you for this post. I will pass it on.

One of my client’s accounts kept being hacked on Twitter. It’s my understanding the company has only 45 employees despite the capital invested. They should spend some on Customer Service.

My biz partner + I tried for weeks to stop the hacking (finally stopped) but telling clients social media experience is important + then not being able to show them their Twitter stream because it keeps getting hacked (this is a Global brand) begs the question of credibility with the client.

This part – and the malware issue my biz partner also had to deal with last week is the truly ugly side ofhaving come to rely on tech.

Hope things straighten out fast for you.

-Barbara

Dan Phiffer

I think the central point is you have some recourse with the water company because you’re paying them. That payment, and the terms they’re operating under, obligates them legally to make sure you’re getting access to water.

This same sequence of events happened to me recently and I also feel pretty uneasy about the role Google is playing in all this. They are a private entity providing public goods. What if Google were to incorrectly list a competitor’s site as a malware provider?

There’s been a lot of talk about Twitter being too centralized technically, as a single point of failure, but never from a customer service perspective. It was a good 20 days before my account was un-suspended. Improving this isn’t a priority for Twitter and I don’t blame them.

c.libre

On the other hand, the opacity of shortened URLs is exactly why they are so troubling. They not only circumvent Twitter’s ability to detect malware, they hamper everybody’s ability to spot suspicious URLs.

A more analogous situation might be the cascading failures that can occur with credit reporting errors.

Isaac Z. Schlueer

If there was a phone number that you could call and get your site off the blacklist, then what’s to stop it from being inundated by malicious spammers?

I agree with Gerald that Google is actually doing the right thing here. Twitter is clearly not making a good-faith effort to index and block spam effectively. The fact that url-shorteners get around the issue is very telling; do they think that spammers have never heard of bitly or trim?

Matt Cutts

We (Google) talked about the notion of advance notice for sites serving malware a little bit at http://googleonlinesecurity.blogspot.com/2008/10/malware-we-dont-need-no-stinking.html . The relevant part is

“I often hear webmasters asking Google for advance warning before a malware label is put on their website. When the label is applied, Google usually emails the website owners and then posts a warning in Google’s Webmaster Tools. But no warning is given ahead of time – before the label is applied – so a webmaster can’t quickly clean up the site before a warning is applied.

But, look at the situation from the user’s point of view. As a user, I’d be pretty annoyed if Google sent me to a site it knew was dangerous. Even a short delay would expose some users to that risk, and it doesn’t seem justified. I know it’s frustrating for a webmaster to see a malware label on their website. But, ultimately, protecting users against malware makes the internet a safer place and everyone benefits, both webmasters and users.”

We do alert webmasters via our webmaster console at google.com/webmasters/ and by marking malware in our search results, but we don’t provide advance notice to sites for the reasons above–it would mean that regular users could be infected while we waited for the webmaster to respond.

Ian Bogost

Matt: thanks for your comment. For what it’s worth, Google never emailed me. But more to the point, even if Google chooses to mark a site as dangerous immediately, the way that they do so is onerous. Don’t you think that the a majority of malware is the result of hacks? Doesn’t it seem reasonable to distinguish different sorts of trust for your users? Isn’t it reasonable to imagine that Google would be able to develop algorithms to guess whether a site is just a malware distributor or, based on previous indexes and other factors, a trustworthy site that probably got hacked? Such distinctions might also help third-party sites, like Twitter, that use the malware notice in a sort of wonky way, to make better decisions.

Even if one brackets the questions of Google’s power over information, the implementation of this feature seems clunky and unsophisticated. Don’t you agree?

Matt Cutts

“Don’t you think that the a majority of malware is the result of hacks?”

I wish that were the case, but in my experience a great deal of malware is deliberate. You’d be surprised at how many people around the world we see who set up web sites specifically for infecting innocent users.

“Isn’t it reasonable to imagine that Google would be able to develop algorithms to guess whether a site is just a malware distributor or, based on previous indexes and other factors, a trustworthy site that probably got hacked?”

The problem is that a small (but growing) number of malware providers attempt to look like innocent hacked sites. Presumably they do so in the hopes that their sites will remain undetected or will stay up longer.

So the short answer is that it’s much easier to make a “is this site hosting malware?” determination than to infer the reasons behind why the malware is on the page. And the bottom line is nearly the same: our end goal is to detect malware quickly and accurately, then unflag the site quickly after the malware is no longer on the site.

It sounds like Google cleared the malware flag relatively quickly, and browsers are set to refresh their data quite fast as well. So in this case, it sounds more like Twitter could have refreshed their downloaded information faster and that would have helped quite a bit.

Ian Bogost

Matt, thanks again for offering more comments. Perhaps you can understand why many reasonable people are bothered by Google’s implicit power. Things like this are not just related to what Google does or doesn’t do, but also how those actions have repercussions.

Twitter just restored my account, so clearly it didn’t take them the 30 days they advertised. Nevertheless, it was inconvenient and perhaps even embarrassing in the interim.

But my interest in this topic has more to do with the implications of Google’s malware detection system than it does with issues of customer service and account management. I’d hope you would also want to consider such matters.

Nick LaLone

The phrase “better safe than sorry” seems to permeate Google in a myriad of ways. In most cases I agree with them, blanket statements that save rather than harm most people probably serves “the greater good”. Horror stories from the other side (your side) tend to remind us that blanket practices often have reprecussions. It seems like a give and take relationship in much the same way as most things are that involve massive amounts of people.

That these things are in the hands of one person, or company, is not only a testement of the pure and awesome might of capitalism (phenomenal cosmic power), but also a reminder that perhaps we need to be more mindful of things when companies like Google begin controlling so much of a market that their forced removal through monopoly legislation would be more harm than good (itty bitty living space).

Perhaps if ICANN or the United Nations manages to gain some pull on the net we can start having more world based legislation to regulate this sort of thing. But that would open a whole new can of worms.

Mark J. Nelson

This reminds me a bit of some of the debates over spam blacklists. With the good ones at least (not all of them), the blacklist providers do a pretty good job specifying exactly what their list contains, keeping it up to date, and providing some information on what you should use it for. But they inevitably get used for a cascading set of other things, often not very carefully and not updated as often. So who’s to blame for that? Depends on your viewpoint I suppose.

In this particular case, Google doesn’t seem hugely at fault, if you consider them in total isolation: they flagged a site as having malware, which from their perspective is purely a matter of search results; and then they unflagged it quickly when it was fixed. The problems seem to be the “cascading failure” that’s the title of this post. Shouldn’t the blame there go to the cascaders, who blindly trust Google’s data, in this case for things it wasn’t necessarily actually intended for? Twitter seems particularly at fault here; I’m not sure automatically suspending accounts associated with Google-flagged malware is a sound policy that minimizes false positives, especially since, unlike Google, they don’t seem to have a quick, automated way of clearing them again.