There’s a nice persuasive game making the rounds, called Spent. It was made by ad agency McKinney for the Urban Ministries of Durham.

The game attempts to illustrate how easily financial hardship and low income work can devolve into homelessness. It does a pretty good job, too, taking the same basic method as did Tenure, the 1975 PLATO game about high school teaching that I discuss in the opening pages of Persuasive Games. The player has to make it through a month without going broke. Each day, a new challenge is presented, typically requiring a choice from a few items. For example, the player’s child might want to join an after school sports team, but to do so would require the purchase of a uniform. The game flashes interstitial facts after these choices, almost all of which are annoying and superfluous; the game does a fine enough job presenting the implications of its choices. It’s not nearly as complex or permutational as Tenure, but for a pro-bono online ad campaign, it’s head and shoulders above most games of this sort.

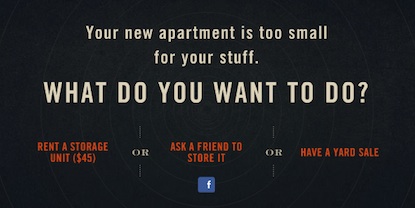

All that is just context for the one feature of the game I want to discuss: certain choices offer the option to ask a friend for help. Here’s one:

In this case, since I’m moving into a smaller, more affordable home, I need to store or get rid of some of my things. My virtual stuff doesn’t really matter much in the game, so there’s no good strategic advantage to holding onto it. But the player can imagine the sentimental value of possessions, not to mention the shock of disposing of them for the rest of one’s family.

As you can see, the game appears to require the player to use Facebook to make the request. In theory, this is a brilliant example of procedural rhetoric in practice. In the real world, asking a friend for help might offset the trauma of selling one’s possessions for next to nothing, and it might avoid the cost of putting them in storage. In this case, the use of Facebook’s social sharing feature appears to act as a muted simulation of the shame that I’d experience in real life by making such a request. It’s a fantastic inversion of the typical advertising use of social media: to spread ideas without social cost or consequence. In this case, the game appears to know that social sharing for benefit is inherently shameful, and it couples a simulated gameplay feature to that real-world emotion.

Or it would have done, had the game really implemented the feature. What happens instead is this: a Facebook share window opens, but the game just continues. The player doesn’t even have to post the request to his or her Facebook profile, let alone wait for someone to make good on the request (which, to cash out the shame-for-benefit idea, would have to entail some sort of real burden for the friend).

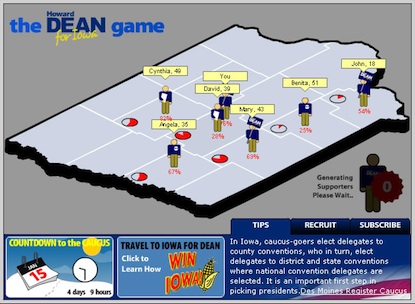

When we made the Howard Dean for Iowa Game back in late 2003, we included a prescient social gaming feature long before that phrase had any meaning. It worked like Spent‘s sharing feature ought to have done, albeit with different communications systems.

The Howard Dean game was all about building a group of supporters through grassroots outreach. You could do that by playing outreach minigames to harvest new supporters, or you could recruit friends as supporters (who would then do simulated outreach work) by sending them emails or instant messages. We rigged it so that all this could be done within the game, and we closed the loop (even on the IMs), so that you had to make contact of a particular kind with a friend before that person would be added to your supporters in the game. It was a simple implementation of simulated social pressure, but a coherent one. After all, canvassing for a candidate requires one to swallow one’s pride and make contact with friends and strangers alike.

Lately I’ve been lamenting the fact that the “social games” aspect of games like Howard Dean for Iowa has taken center stage, rather than the “persuasive games” aspect of such games. But Spent doubles that lamentation, by reminding me that the two could work in tandem, by coupling social action with simulated results.

Comments

Danny miller

Hmm, does one even remotely feel the shame of asking a friend to store real stuff when asking a facebook friend to store virtual stuff? Even if it did post to wall the only shame would be the shame of posting a facebook app message.