In the mid-1980s, the easiest way to check out the latest computer games was to go to a bookstore in the mall. Past the John Grisham and the bargain history books in the B. Dalton Bookseller, you’d find Software Etc., a small island of boxes amidst bound volumes, and a few computers on which to play the latest releases. It was there that I first played Dark Castle, a 1986 Macintosh game about manipulating the then-unfamiliar mouse to throw rocks at bats.

Software Etc. eventually moved into its own mall storefront. Years later, after a series of sales and mergers, it would become GameStop. But back then, in the late 80s, the aesthetic and sensibility of a bookstore remained at Software Etc. This was an intellectual space, of a sort, where ideas took form in bytes on disk rather than words on a page. And where they could thrive, too. (Dark Castle’s success would help one of the duo who made it, Jonathan Gay, pay for college at Harvey Mudd. Later, he made FutureSplash Animator, which became Flash, the web animation and interactivity tool that ruled the web from 1996 until the rise of the smartphone.) It was there, in the B. Dalton Software Etc., that I first played SimCity, Will Wright’s classic city-building game. It was 1989, and the game was running on a black-and-white Macintosh computer in the mostly empty store.

From today’s vantage point, it’s hard to explain how strange SimCity felt back then. The game that started with nothing, an empty map. Stupidly, I placed a square residential sector in the very top left, mistaking the barren, terraformed environment for something akin to a word-processing document. Then another, then some roads, forming a rudimentary grid. They remained empty, flashing their disapproval. I had no idea what I was doing.

By the time I realized that the residential districts required access to electrical power, some of the game’s more complex dynamics suddenly piped in like Muzak from the store’s beige walls. I figured out how to select a power plant from the game’s toolbar (this was years before I’d use Photoshop) and realized: Nobody wants to live next to a power plant. I resolved to place my coal plant (the only one I could afford) further down the map, and then connect it back to civilization with a meandering path of power lines. The question of what to do stuck with me, even though I had to leave the mall and abandon my fledgling city.

Such was the payload of SimCity: not a game about people, even though its residents, the Sims, would later get their own spin-off. Nor is it a game about particular cities, for it is difficult to recreate one with the game’s brittle, indirect tools. Rather, SimCity is a game about urban societies, about the relationship between land value, pollution, industry, taxation, growth, and other factors. It’s not really a simulation, despite its name, nor is it an educational game. Nobody would want a SimCity expert running their town’s urban planning office. But the game got us all to think about the relationships that make a city run, succeed, and decay, and in so doing to rise above our individual interests, even if only for a moment.

This was a radical way of thinking about video games: as non-fictions about complex systems bigger than ourselves. It changed games forever—or it could have, had players and developers not later abandoned modeling systems at all scales in favor of representing embodied, human identities.

* * *

Last week, as 25,000 game-industry professionals gathered in San Francisco for their industry’s annual Game Developers Conference (GDC), Electronic Arts shut down SimCity creator Maxis’s Emeryville studio, near Oakland. EA had bought Maxis in 1997, and the studio had enjoyed furious growth and influence in the ensuing decade as its virtual dollhouse The Sims rose to prominence, before faltering after the modest success of the highly-anticipated 2008 “everything simulator” Spore. The 2013 release of a reconceptualized SimCity also cost the studio goodwill and revenue, as early players were subjected to a badly malfunctioning, compulsory server connection.

Will Wright created the first prototypes for SimCity after realizing that he enjoyed generating levels for a helicopter combat game more than making the game itself. He adopted some of the urban dynamics models developed by the MIT systems scientist Jay Forrester, adapting them into a “software toy,” as Wright called it, that used cellular automata to percolate the effects of land value, pollution, utilities, and more throughout a model of an urban environment. The city itself, with its tiny cars and varied buildings, are really just visualizations of the underlying simulation, a kind of clever way to see the city running, rather than the city itself.

All of Wright’s games at Maxis followed this model. A software toy, grounded in a worldly theory about a complex system, but abstracted into a playable model about an aspect of the world that seemed too boring or obscure to become the subject of a video game. SimEarth was inspired by James Lovelock’s Gaia principle, which understands the Earth as a single, self-regulating organism. SimAnt was based on Bert Hölldobler and E.O. Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Ants, on the social organization of ant colonies. The smash hit The Sims, often described as a virtual sandbox, was really far more than that, operationalizing Christopher Alexander’s theory of a pattern language for architecture, Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and Paco Underhill’s investigations into the rationales behind consumer behavior. Even the seemingly fantastical Spore had a similar grounding, mostly in Lovelock’s lesser-known Gaia spore, the theory that intelligent life is more likely to reproduce itself in the universe through space colonization than it is to evolve anew from nothing.

Maxis’s games have hardly escaped criticism. Game design is a process of abstraction, and you can’t simplify a complex system like the operation of cities without consequence. SimCity was profoundly but weirdly American in its assumptions. Taxation caps out at 20 percent, a level far below what would be needed to operate a social welfare state city like, say, Copenhagen. And at higher tax levels, Sims go on strike or move out of town in disgust. But even in such a seemingly American context, race plays no role in the operation of one’s simulated cities, and the classic features of American sprawl—highways, exurbs—weren’t possible in the earliest versions of the game, even as rail transit has always remained the best way to reduce traffic and increase density in a SimCity metropolis. The game’s most recent version did even stranger things, casting residents as a kind of bizarre blend of middle class laborer and migrant worker, and making homelessness rampant, causing players to reveal curious and sometimes uncomfortable truths about themselves and the world in their quest to (virtually) eradicate it.

Such matters are less problems or defects than they are features of games made to characterize the world according to a creator’s viewpoint, interests, caprice, or ideology rather than to simulate its behavior in full—as if such a thing were even possible. When we build a game in Wright’s style, we make a simplified, abstracted model of something that attempts to characterize how that thing works, in some way.

* * *

In at least one case, the 1994 title SimHealth, Maxis attempted a title of this sort that would soon after be called “serious games.” A complex management simulation of the U.S. healthcare system, SimHealth was released amidst debate around then-President Bill Clinton’s proposed Health Security Act, an attempt to reform U.S. healthcare in ways that wouldn’t be taken up again until Obama’s Affordable Health Care act.

SimHealth was never a hit, but titles like it would be tremendously influential to me as a game designer. Eventually, at my own fledgling studio, I’d make games about all sorts of things, things that never would have occurred to me as possible topics for games had SimCity not come first: political canvassing, data compression, tort reform, wind energy politics, disaffected workers, airport security theater, fast food franchise economics, the global petroleum market, food import safety, immigration legislation, personal debt, the politics of nutrition, and more. I developed my own design philosophy that I called procedural rhetoric, an unholy blend of Will Wright and Aristotle. In these games, players experience a model of some aspect of the world, in a role that forces them to see that model in a different light, and in a context that’s bigger than their individual actions.

The best games model the systems in our world—or the ones of imagination—by means of systems running in software. Just as photography offers a way of seeing aspects of the world we often look past, game design becomes an exercise in operating that world, of manipulating the weird mechanisms that turn its gears when we’re not looking. The amplifying effect of natural disaster and global unrest on oil futures. The relationship between serving size consistency and profitability in an ice cream parlor. The relative unlikelihood of global influenza pandemic absent a perfect storm of rapid, transcontinental transmission.

And system dynamics are not just a feature of non-fictional games or serious games. The most popular abstract games seem to have much in common with titles like SimCity than they do with Super Mario. Tetris is a game about manipulating the mathematical abstractions of four orthogonally connected squares, known as tetrominoes, when subjected to gravity and time. Words With Friends is a game about arranging letters into valid words, given one’s own knowledge merged with the availability and willingness of one’s stable of friends. A game, it turns out, is a lens onto the sublime in the ordinary. An emulsion that captured behavior rather than light.

* * *

But making games about complex systems instead of tanks or plumbers or hedgehogs or soldiers was always a long-shot. Culturally, video games are often cast aside as vulgar and flagrantly violent. They’re maligned as pointless drivel serving no purpose and simultaneously criticized for encouraging outrageous, irresponsible behavior and delinquency. Some will concede, at best, that video games offer harmless distraction, like the idle dream of being a professional football player. These perceptions come from the same place as video-game advocates’ own love for the form. Games are a place to escape, a place to be powerful, a place to have agency in a world that so often wrests it from us.

These are the most popular and often the most beloved titles of our art—Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty and Halo and Destiny and Assassin’s Creed and even FIFA and The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario Bros. These are the games for which joysticks were invented, in which players pilot characters around spaces to hurl or avoid projectiles. And usually, those characters are of a singular kind. Big, burly, furrow-browed men (or cartoons of men) with a grudge.

Male video game protagonist bingo cards! Created by @wundergeek who also has a nifty Patreon: https://t.co/I5QIe0v72E pic.twitter.com/1l4NSLgzbR

— Feminist Frequency (@femfreq) March 9, 2015

At this year’s Game Developers Conference, the educator Rosalind Wiseman and the game voice artist Ashly Burch presented results from a survey of students between the ages of 11 and 18, suggesting a marketplace exists for diverse characters that the industry is ignoring. Among their findings, less than 40 percent of high-school boys preferred to play as male characters, while 60 percent of girls preferred female ones. Wiseman and Burch encouraged developers to offer more diverse characters, noting that women and girls are more valuable customers than the industry believes. For years now, others have made similar appeals for better representation of minorities of all stripes, both in games and in game development. If we must have characters in games, let’s do make them represent the diversity of their players and of our society. And if we must make games at all, let’s see them created by developers who represent the diversity of their playership.

But, an unpopular question lingers, one that Maxis’s closure calls to mind. Why must we have characters in games at all? Or, more gently put, why have we assumed that the only or primary path to video-game diversity and sophistication lies in its representation of individuals as opposed to systems and circumstances? In truth, we’ve all but abandoned the work of systems and behaviors in favor of the work of individuals and feelings. And perhaps this is a grievous mistake.

Maybe the obsession with personal identification and representation in games is why identity politics has risen so forcefully and naively in their service online, while essentially failing to build upon prior theories and practices of social justice. And perhaps it is why some gamers have become so attached to their identity that they’ve been willing to burn down anything to defend it. Surely a better understanding and appreciation of these underlying systems (not the least of which involves the corporatized Internet that has offered such an effective accelerant for grotesquerie) would have raised the question of how and why the gamer identity became cherished to the point its advocates would be willing to sabotage its progress in the public imagination. Surely it would have stymied the sense of entitlement among gamers who have sought to exclude anyone—particularly women—who challenge their ideas about what games and gamers look like. The very idea of the gamer assumes that identity is predominant, even before that identity seeks either protection or expansion. And then, for everyone, games primarily become an apparatus for exercising self-identity rather than just a kind of media, like the books and magazines that filled the B. Dalton.

* * *

In truth, the closure of Maxis Emeryville means little for the future of the studio’s franchises, which had been rolled up into EA’s general management years ago. Wright left the company in 2009 to work on projects at his Stupid Fun Club, a Willy Wonka-version of a think tank whose output remains mysterious and largely hypothetical. But the end of Maxis does seem to mark the popular conclusion of Wright’s style of software toy simulation and the design model for games it represents. Its progeny continues, to be sure, but not at the same scale and influence.

The assumption that games are a medium of individual identification that would provide self expression and personal validation, as Wiseman, Burch, and others hope, is an unexamined ideology. Why not ask, at least, why we should bother? Other narrative media succeed more often and more profoundly at producing identification and empathy with individuals of our own creed, color, gender, and sexual identification—or with those of other identifications. Sure, film and literature and television also have problems with representation, but their character-driven narratives match well to their forms. Yet, alas, at their best, game characters and game stories are still mostly like bad books and films and television, but with button pressing. Perhaps the only reason not to let these other media do the work they do best is if we fancy games a world unto itself, a private media ecosystem.

There’s another way to think about games. What if games’ role in representation and identity lies not in offering familiar characters for us to embody, but in helping wrest us from the temptation of personal identification entirely? What if the real fight against monocultural bias and blinkeredness does not involve the accelerated indulgence of identification, but the abdication of our own selfish, individual desires in the interest of participating in systems larger than ourselves? What if the thing games most have to show us is the higher-order domains to which we might belong, including families, neighborhoods, cities, nations, social systems, and even formal structures and patterns? What if replacing militarized male brutes with everyone’s favorite alternative identity just results in Balkanization rather than inclusion?

Around the same time SimCity appeared in 1989, games were split between the childish Nintendo and the nerdy personal computer. A decade later, Doom had opened the door to first-person power fantasies, Madden had become more realistic and less cartoony, Sony’s PlayStation offered older kids and adults a return to games after having abandoned them as toys, and Myst and Bejeweled took over the hearts and minds of ordinary people who enjoyed playing them but might never have called them “games.”

Maxis’s hit of the early 2000s, The Sims, offers an exception to all of these predecessors. It would appear to offer all the representation and identity that would appeal to contemporary critics, but in practice, The Sims resists representation and identification. One can’t really control one’s Sims, except on a moment-to-moment basis, directing them to the bathroom or the television, gardening at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

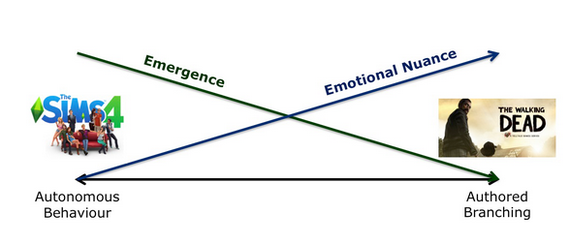

In a Game Developers Conference talk on social simulation delivered the same day the news of Maxis’s shuttering arrived, Mitu Khandaker-Kokoris, the creator of the sci-fi social networking simulation Redshirt, theorized a continuum of social Sims. On one end she locates The Sims, which exemplifies emergence—that is, a complex, unexpected result that arises from the unforeseeable interactions of smaller, autonomous components. Emergence is what makes it possible to produce seemingly deep stories or relationships between Sims from relatively innocuous individual instructions, like “read a book instead of watching TV.”

Khandaker-Kokoris opposes the unexpected sublimity of emergence to the predictability required for emotional nuance, toward which the other end of the spectrum trends. This is the depth that only deliberate, human-authored stories can provide. Telltale’s acclaimed adaptation of The Walking Dead graphic novels exemplify this latter sort of title (in video games, emotional nuance often seems to involve zombies).

Khandaker-Kokoris explicitly rejects the idea that one or another part of the spectrum bears greater value or promise for games or for players. Instead, she comes to the same conclusion all the best systems thinking always does: It depends. It’s complicated. There are lots of tools, lots of styles, lots of ways to make games about people. Human representation and identification is itself a system, one without clear answers and without sure outcomes.

But. Let’s stop just short of letting absolute inclusivity—an unattainable goal—once again rule the roost. Let’s resist the assumption that social inclusivity entails absolute inclusivity, such that all ideas are utterly fungible, one as good as any other in any context, such that doing what feels right or pleasurable or comforting is what’s best. To oppose “emotional nuance” to the surprising, unpredictable depth of simulated systems means we’re talking about a very particular kind of emotional nuance, one focused on connections between individual human beings rather than on affiliations with systems of all sorts—people, cities, ecosystems, universes. So let’s take the opportunity that Maxis’s symbolic demise represents to mourn the decline of the video game as operable argument, as machinery that shows us something about the world outside ourselves, something incomplete and grotesque even, but something we ought to see.

* * *

EA will continue to make and release SimCity and The Sims titles so long as those names remain relevant to contemporary players—hardly a guarantee. But the Maxis office in Emeryville was a symbol, a modest SimCity monolith to Wright-style playable simulation. EA, based an hour south in Redwood Shores, tried to move Maxis down to Silicon Valley more than once, but Wright always resisted, preferring the East Bay and its surrounding hills where he had long lived and worked. A particular urban location, in other words, mattered to Wright. Making simulations like SimCity wasn’t just knowledge work that could be done anywhere; it was situated. It’s unlikely that players of Maxis’s games realized, until now, that simulation had an unlikely home nestled in between Berkeley, the cradle of identity politics, and the rising glass towers of San Francisco’s SoMa, where the new Silicon Valley has set up shop—Twitter and Dropbox and so many other members of the data speculation industry that has overtaken this city on its way to overtaking the world.

Perhaps there is warning there, within a bigger system, among a different cabal of people playing at being gods. Amidst arguments on Twitter and Reddit about whose favorite games are more valid, while we worry about the perfect distribution of bodies in our sci-fi fantasy, the big machines of global systems hulk down the roads and the waterways, indifferent. It is an extravagance to worry only about representation of our individual selves while more obvious forces threaten them with oblivion—commercialism run amok; climate change; wealth inequality; extortionate healthcare; unfunded schools; decaying infrastructure; automation and servitude. And yet, we persist, whether out of moralism or foolishness or youth, lining up for our proverbial enslavement. We’ll sign away anything, it would seem, so long as we’re still able to “express ourselves” with the makeshift tools we are rationed by the billionaires savvy enough to play the game of systems rather than the game of identities.

Only a crackpot would claim that SimCity could have saved us, or that games inspired by the systems simulation model could have overcome the overwhelming, ongoing success of stories and images that computers merely deliver via digital channels, rather than reformulating into systems made playable in software. But then, only a fool would fail to realize that we are the Sims now meandering aimlessly in the streets of the power brokers’ real-world cities. Not people with feelings and identities at all, but just user interface elements that indicate the state of the system, recast in euphemisms like the Sharing Economy, such that its operators might adjust their strategy accordingly. No measure of positive identification can save us from the fate of precarity, of automation, of privatization, of consolidation, of attention capture, of surveillance, of any of the other “disruptions” that cultivate our culture like bulldozers click through sim cities. To pursue an alternate future, we’d have to change how the machine works, not just the faces of its operators. But to change how the machine works, we’d have to admit that it is bigger than us, and that no measure of comfort in our own skin can protect that flesh from its honed gears and its obdurate treads. Being ourselves, it would seem, is the danger video games might have helped us overcome.