What follows is the text of my keynote at the 2009 Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) conference, held in Uxbridge, UK September 1-4, 2009. The text corresponds fairly accurately to the address I gave at the conference. In a few cases, I’ve added some clarifications in square brackets, where additional context or commentary was relevant.

So much of videogame studies has been marked by a single question: “What is a game?”

For a while now, our community has understood that “mark” as a curse or a blight—a scourge of formalism that drew, or perhaps still draws, our attention away from more important matters of meaning, reception, and use.

Today I’d like to return to this question, “What is a game?” in the hopes of reminding us what it really is: not a strategic, rhetorical, or political question, at least not primarily so. Rather, it is an ontological question. It is a matter of metaphysics, not a matter of field-building. Perhaps it’s time we treated it as such.

Let’s briefly review a few key moments in our history as a field before returning to the problem of ontology more directly.

Once upon a time, the question that captured our collective imagination (and ire) was this one:

Is a game a system of rules, or is a game a kind of narrative?

We liked this question so much that we even developed a nickname for it:

Ludology vs. Narratology

Like many of you, I’ve made a number of observations about this matter before. Most notably, we should remember that it was the so-called ludologists who choose these terms, and they did so with great élan.

For starters, what a word! Ludology. In all its latinate glory, it imposes a kind of seriousness upon this then-even-more-unseemly act of studying videogames for a living. It was historical too, drawing from both Huizinga’s and Callois’s use of the term ludus. It felt almost like something you could imagine seeing on a diploma or a business card.

As Gonzalo Frasca tried to remind us at the very first DiGRA conference six years ago, but as we could tell ourselves anyway from his 1998 DAC paper “Ludology meets Narratology,” these two concepts were never intended to be opponents in the way a Las Vegas marquis-worthy label like “Ludology vs. Narratology” suggests. Narratology was less a Piston Honda to ludology’s Little Mac than it was a Doc Louis, riding its bicycle ahead and egging on the frail and underdeveloped hero that was game studies.

As Frasca observed, games were the underdogs: “Traditional games have always had less academic status than other objects, like narrative,” he rightly offered. The ludological proposal did not involve entering into a heavyweight bout against narratology, but to learn from it, to use it as a kind of model for how objects of study become legitimate and how the study itself becomes mature. Just as narratology had developed to address narrative, so must something new develop to address games.

The problem is, the entire move was a trick. Frasca argued that “the term narratology had to be invented to unify the works that scholars from different disciplines were doing about narrative.” Ludology was supposed to do the same for games. Such a move was supposed to fix a “major problem” in the study of games, according to Frasca: “lack of clear definitions and theories; more functionalist approach rather than formalist; fragmented analysis from different disciplines.”

But Frasca gets narratology wrong. It was never a term that unified scholars from different disciplines; indeed, narratology remains a very particular structuralist approach to the study of narrative—not story mind you, but the differences between stories and their telling. Frasca would have been better off saying that “traditional games have always had less academic status than other objects, like sea scallops.” Such a statement might have generated less misunderstanding.

Yet shifting the frame of “narratology” hid the real agenda: a move toward a formalist rather than functionalist approach to the study of games. In this sense, Frasca’s title, “Ludology meets Narratology” offers the first shadow of the wool as it was pulled over our collective eyes: such a “meeting” shouldn’t have seemed surprising at all. The idea of one formalist analytical method meeting another is more like an attorney reinventing himself as a legislator than it is like a mime transforming into a urologist. A careful turn of phrase effectively reframes a discourse to invent a conflict it can never lose. It’s like the scene in The Blues Brothers when Elwood asks the bartender Claire at Bob’s Country Bunker, “What kind of music do you usually have here?” And she responds cheerfully, “Oh, we got both kinds. country and western.”

I belabor this point to draw attention to the real goals underlying the so-called ludology vs. narratology debate. By pitting one kind of formalism against another, the result became a foregone conclusion: formalism wins. Really, it doesn’t even matter which one, since the underlying assumptions are so similar. The ludology/narratology question may have appeared to look like this:

Is a game a system of rules, or is a game a kind of narrative?

But really, it amounted to something more like this:

Is a game a system of rules, like a story is a system of narration?

The disjunction is gone, and the answer is implied (yes). David can put down his sling and toss the stones back into the brook.This first ontology of games is really a rhetoric, not an ontology at all. It reminds me of Žižek’s comparison of the Iraq war to Freud’s anecdote of the kettle.

Here let’s take note of the first move in videogame ontology: the suggestion that the ontology of games is an ontology of form: the study of the structures and systems that undergird games overall, genres or types of games generally speaking, and particular examples of games in particular.

As Espen Aarseth, Michael Mateas, and others have observed, a better characterization of the “narratology” corner is something like “narrativism,” which Aarseth describes as “the notion that everything is a story, and that story-telling is our primary, perhaps only, mode of understanding, our cognitive perspective on the world.” Narratology is a formal method for analysis, one that actual critics deploy in the study of actual story systems and artifacts; narrativism is an ideology that is never used, but like all ideologies only sits in the background driving choices that its interpellated subjects are unable even to see.

Another move, simultaneous with the advance of ludology but also extending beyond it, always admitted that games seem to have much in common with storytelling. Frasca begins his early piece on ludology with the “many elements” games share with stories, including “characters, chained actions, endings, settings.” In the same year 3D Realms began development on Duke Nukem Forever, Aarseth wrote, “To claim that there is no difference between games and narratives is to ignore essential qualities of both categories. … the difference is not clear-cut, and there is significant overlap between the two.”

The most notable extension of this idea would come from Jesper Juul, who backed away from ludology as borrowed kettle to argue that games are made of both rules and fiction. Here we see an important turn away from narratology as formalism and narrativism as ideology, and an embrace of a more pragmatic approach. As Juul says in Half-Real:

“…video games are two rather different things at the same time: video games are real in that they are made of real rules that players actually interact with; that winning or losing a game is a real event. However, when winning a game by slaying a dragon, the dragon is not a real dragon, but a fictional one. To play a video game is therefore to interact with real rules while imagining a fictional world and a video game is a set of rules as well a fictional world.”

Two moves are at work here. First, there is a new embrace of syncretism, one suggested rhetorically by Frasca, Aarseth andothers but never carried out in earnest. Games, argues Juul, can be both ludic and fictive, without giving up either their systemic nature or their fictional one.

Second, a twinge of gradation emerges. For Aarseth and Frasca, narration, character, and other story-derived elements exist in games, but the firmament of the thing is formal: a system of rules underlying them. When all else is stripped away from a game, says Aarseth, “the rules remain.” For Juul, the matter is slightly more nuanced, but nevertheless we see the prow of an ontological pecking order emerging over the horizon.

Both Aarseth’s mildly invective narrativist position and Juul’s more sincere syncretic one on rules and fictional worlds make a common move:

Whatever a game is, some part of it is more real than another.

Here we can see a new turn in the ontology of games, the one that nobody seems to talk about: a conflict of idealism vs. realism. We can take some pleasure in the fact that this problem has been around for thousands of years in metaphysics, and that it nevertheless remains a popular beard-stroker. It poses the following question: is the nature of reality based on ideas in our minds, or does it exist separately and independently of knowledge and consciousness?

In this case, rather against the grain of contemporary thought, Aarseth and Juul take an implicitly realist position about games, but a troubled one. It is not a simple notion of fixed independence, but what philosopher Lee Braver calls correspondence (A Thing of This World, pp. 15-16): truth involves some sort of correspondence between thought and real things. In both Juul’s and Aarseth’s positions, we find a tiered distinction. The formal structures of rules are real, and things like fictions and stories and the overall experience of those rules are byproducts to be found in the act of play, and in the minds of players.

Here we also find the traces of a more familiar response to idealism, that of Kantian transcendentalism: sure, the mind pollutes our experience of reality, but that’s ok: our knowledge of the world does not reflect things in themselves, but to our perceptions’ correspondence with principles already extent in the mind. We could read Aarseth’s and Juul’s positions in both ways: either as a straightforward correspondence theory of realism, or as a transcendental idealism wherein things like stories result from the reasoned perception of an already extant idea of rules. In any case, one thing is sure: there are some parts of games that are more fundamental than others, and some that are the mere epiphenomena of subjects.

We find similar moves at work in literature on game design. In Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek’s Mechanics Dynamics Aesthetics (MDA) model of game design, the “aesthetics” or experience of a game is produced by the player’s interaction with “dynamics,” which are in turn produced by the designer’s construction of mechanics (or rules) whose emergent behavior produce those dynamics. Here we find the same weird confluence of correspondence and transcendence: the reality of a game is a construction of player perception, but that construction exists more fundamentally, at some level of depth that corresponds with mechanics.

An aside: In another move we’ll hear about tomorrow [in the context of the conference, that is], Michael Mateas and Noah Wardrip-Fruin advocate a notion that sits at a higher order than mechanics. They call this idea “operational logics,” which I’d describe as the structures that enable particular mechanics in the first place.

Anyway, let’s call this the second move in videogame ontology: the suggestion that games exist on multiple levels, but some are more real than others. At least some of these levels are mental constructions while others are material firmament, and games are real at their formal levels, but that such reality is more transcendental than it is really real.

More recently, Juul has offered another take on the current state of game scholarship. The old problem of ludology and narratology has passed, he argues, and in its place we find a new one, which he calls the Game/Player Problem. In short, asks Juul, should players or games be the object of study? The distinction is simple enough: the game-centric view argues that the gameplay drives what the player can do, while the player-centric view argues that everything that goes on in gameplay is driven by the player.

Juul’s observation also underscores the rise of social science, studies focusing on the social practices of game players, such as the differences between play in an American den and a Korean PC Baang. Because such approaches find of their interest in players over games, they also arose to help explain multiplayer experiences like MMOGs. We might also bundle into the games/players conundrum the rarer perspectives on games as political economy and ideology. I think in particular of the work of Alex Galloway and McKenzie Wark.

For Juul’s part, he identifies two positions on the matter, calling one “segregationist” (“games are structures separate from players”) and the other “integrationist” (“games are chosen and upheld by players”). Here all sorts of other factors come into play, so to speak, that wouldn’t normally be accounted for under earlier formalisms or narrative accounts of games. Juul offers some examples, from the charming and sad animated story of a player’s relationship to her dying mother via Animal Crossing to the very choice of what game console one buys and what games are available for it. Here we also find other hybrid work, like Michael Nitsche’s theory of game space, in which the space of play (that is, things like the couch and the rug and the television stand) serve roles that can be as important as the rendered in-game space, or even more so.

As the vaguely derogatory and historically charged label “segregationist” suggests, I think Juul means to argue that games are better thought of as confluences of players and games, but it’s hard not to see an implicit move in this line of thinking: games are really just limp skins that may exist, but only in lesser form, until they are filled out and activated by players.

Let’s call this the third move in videogame ontology: the suggestion that games exist when players occupy them and give them life by reallocating formal properties according to their own particular personal and play contexts.

This move, I’d argue, is a pretty straightforward adaptation of metaphysics after Kant’s Copernican Revolution, in which things primarily or exclusively exist for humans, and that things may exist, but thinking of those things apart from their being thought is incoherent. The idea of context, dissemination, and variance in player communities comes into strong play, just as it has done in cultural studies for the past few decades.

The last account of videogame ontology I’d like to share comes from my own recent work with Nick Montfort on platform studies. One of the ironies of digital games research, to use the name this conference and organization chooses for itself, is how strikingly absent are things “digital” from our conversations. Ludology, for example, has always prided itself on approaching games “in general.” The same is certainly true of a number of popular accounts of game design, including those of Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, and of Tracy Fullerton.

Montfort and I set out to draw a distinction: videogames are computational artifacts whose understanding demands at least partial mastery of the architecture of computers. More strongly, each videogame is a particular piece of software created and run on a particular piece of computer hardware, at a particular moment in time. Individually and together, these software and hardware systems exert pressure on one another, extending backward toward inspiration and influence and forward toward convention and genre. Such an approach, we hoped, might help support the social, critical, material, and political economic registers upon which we understand software artifacts like videogames. In short, we suggested that a major, perhaps even primary feature of computational media arises from the constraints of hardware and software design.

In the afterword to Racing the Beam, our platform study of the Atari VCS, Nick and I suggest a model for the study of computational creativity writ large. We argue that it can take a number of focuses, and we distinguished between five:

Reception and Operation focuses on the experience of the user, includeing approaches like reader-response theory, psychoanalysis, and media effects studies.

Interface focuses on the user’s relationship to the visible, operable part of a computer system, including the discipline of human-computer interaction, visual, filmic, and art historical approaches to the appearance of games, and methods like Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin’s notion of remediation.

Form and Function focuses on the operation and behavior of the program. This is where we find approaches to the operation of the program. Here is where both ludology and narratology live, by the way.

Code focuses on the way work is programmed and understood by programmers, including software studies and code aesthetics, as well as software engineering and other computer scientific methods for understanding how code works and is constructed.

And Platform focuses on the abstraction layer beneath code. If code studies are new media’s analogue to software engineering and computer programming, then platform studies are its version of computing systems and computer architecture.

Often, we suggest, effective studies of new media will draw from multiple levels of this model. But more strongly, we argue that the level of analysis we call platform is both a promising and underexplored aspect of new media scholarship.

Nick and I took these five layers and floated them in the soup of culture and context, suggesting that each of them finds itself situated in complex relations with human culture and experience. For example, much of our discussion of the hardware design of the Atari involves the context of the business and social practices of 1970s computing. Similarly, important aspects of our discussion of particular games involves the context and culture of work and creativity, including the ways the developers of games like Adventure and Pitfall! negotiated between expressive goals, cultural influences, and the material constraints of the hardware platform itself.

There is a possible objection to this model, one we have certainly heard more than once. Some call it technological determinism, but a more nuanced gripe might accuse us of scientific naturalism instead. For naturalists, the world amounts to sets of ever more fundamental, ever smaller things and parts, and the really-real amounts to the most fundamental. Things induce parts, parts induce elements, elements induce atoms, atoms protons and hadrons quarks and so on. Science aims to get to the bottom of things, and continues digging until a bottom is found.

But the aim of our model is not to argue that platforms are fundamental to games, such that a close study of the hardware, down to the metal, will bring forth a particle rain of certain explanations for all extant games. Rather, it aims to suggest that platforms are an indisputable part of games, and pretending that they are not amounts to provincialism at best, and sheer madness at worst.

It is from this perspective that I’d like to tease out a fourth move in the ontology of games, one that incorporates and responds to all of the others in a way I hope might be satisfying and helpful to all of us.

To get there, it’s going to be necessary to take a quick detour through contemporary metaphysics.

In recent years, a small but increasingly vocal group of philosophers have been assembling a critique of the post-Kantian tradition of ontological anti-realism. As it is relevant to my interests, this critique involves two related moves: first, a rejection of idealism and a reassertion of realism. And second, an expansion of the concern of being beyond the human.

Let’s start with the commonly held view, the one we have lived with throughout the last century, and which we can trace back to Kant’s transcendental idealism. Being, this position holds, exists only for subjects. For Berkeley, it comes in the form of subjective idealism, or the idea that objects are just bundles of sense data in the minds of those who perceive them. For Hegel, it comes in the form of absolute idealism, or the idea that the world is best characterized by the way it appears to the self-conscious mind. For Heidegger, objects are outside of human consciousness, but their being exists only in human understanding. For Derrida, things are never fully present to us, but only differ and defer their access to individuals in particular contexts, interminably. The linguistic turn of mid-twentieth century philosophy continued the preference for consciousness inaugurated by phenomenology, but transitioned that conceit to language.

All such moves consider being as a problem of access, and human access at that. Quentin Meillassoux has coined the term correlationism to describe this view, one that holds that being only exists as some sort of correlate between mind and world. While things can exist for some correlationists, they only do so, in Meillassoux’s account, for-us. The principal example Meillassoux offers in his 2006 book After Finitude is this one: the correlationist cannot accept a statement like “Event Y occurred x number of years before the emergence of humans.”

“No—he will simply add—perhaps only to himself, but add it he will—something like a simple codicil, always the same one, which he will discreetly append to the end of the phrase: event Y occured x number of years before the emergence of humans—for humans (or even, for the human scientist).” (p 13)

While the notion may be intelligible, it is only made so through a cognitive process re-imprinted onto the human past. In the correlationist’s view, both humans and the world are inextricably tied to one another, the one never existing without the other. We find here something similar to Bruno Latour’s critique of modernity: it attempted to split the world into the two halves human and nature. Human culture is allowed to be multifarious and complex, but the natural or material world is only ever permitted to be singular.

Flying the standard of “speculative realism,” Meillassoux and a number of other thinkers have sought to reject correlationism and to re-admit the multifarious complexity of being, as well as to free being from the sole purview of human, returning it to all objects, including the human ones. Reality is reaffirmed, and humans are allowed to live within it alongside the sea urchins, kudzu, tacos, quasars, and Tesla coils.

There are a number of approaches to this task, but my favorite, and the one I consider the most useful for the purposes of clarifying the ontology of games, is that of Graham Harman. Starting from Heidegger’s tool analysis, Harman constructs into what he calls an “object-oriented philosophy.”

Very quickly: Heidegger suggests that objects are impossible to understand as such. Rather, they are related to purposes, a circumstance that makes speaking of hammers or tacos as objects problematic; such objects are ready-to-hand (or zuhanden) when contextualized. Heidegger further argues that objects are most visible when they cease to conceal themselves in these contexts. He calls this state presence-at-hand (or vorhanden). His favorite example is the hammer, which affords the activity of nail-driving, something we look past in pursuit of a larger project, say building a house—that is, unless it breaks and becomes abstracted.

Harman argues that this “tool-being” is a truth of all objects, not just of Dasein: hammer, human, haiku, and hot dog are all ready-to-hand and present-at-hand. He suggests that objects do not relate merely through “human use,” but through any use, including all relations between one object and any other. Here we also find a reply to scientific naturalism: things are allowed equal being no matter their size or scale or order.

There is much more to say about all this, but no time for it right now. You might notice the similarities to other traditions more familiar to our common disciplines, such as Whitehead’s notion of occasions in process philosophy, or Latour’s notion of actors in actor-network theory. But perhaps the simplest way to summarize Harman’s position is to cite the informal addition he offers to Lee Braver’s notions of realism: “The human/world relation is just a special case of the relation between any two entities whatsoever.” I’d clarify that “special” in this case just means a particular, not exceptional.

There is one lap I need to swim before drying us off from our refreshing dip in the pool of metaphysics, and it passes through Levi Bryant’s adaptation of Harman’s object-oriented philosophy into what the former calls flat ontology. This is a term that first occurs in the work of Manuel DeLanda, who uses it to refer to an ontology comprised entirely of individuals (rather than species and genera, for example). Bryant’s use of the phrase is somewhat different: a flat ontology allows all objects the same ontological status. And furthermore, as for Latour, “objects” can mean corporeal or incorporeal entities, including objects of intention: quarks, Harry Potter, keynote speeches, single-malt scotch, Land Rovers, lychee fruit, love affairs, dereferenced pointers, Slavoj Žižek, bozons, horticulturists, Mozambique, Super Mario Bros., all are fair game. If it bothers you to call these things “objects,” you might instead replace it with my term “unit” to the same effect.

Ok, back to games at last. All of the takes on game ontology I’ve shared with you, we find a common property: all state or imply an ontological hierarchy for videogame objects. In some cases, this hierarchy is one of scientism, as in the case of the (mis)reading of the levels of new media, or the relation between operational logics, mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics. In other cases, the hierarchy is one of the nature/world divide of anti-realism, as in the case of Juul’s imagined worlds and real rules, or player applications of games and the games themselves.

If we accept Harman and Bryant’s invitation to flatten the ontological field, such that all objects are on equal footing, the result is a plane of indiscriminate differences, in which all aspects of a game’s existence have the same potential to matter. The question we can then pose is, for a particular game in a particular circumstance, which units matter? Such a strategy frees us from seeking grounds upon which game-objects rest incontrovertibly, prevents us from making short-sighted essentialisms about computer hardware or human experience (or anything in between), and forces us to ask more specific questions about particular analytical situations. It should no longer be satisfactory to seek one answer to the question, “what is a game?”

This is not merely a call for us all to just get along, nor is it an appeal to an indistinct Deleuzean plane of immanence or assemblage. This is not magic nor idle theory. It is a practical approach to thinking the existence of games.

An example is in order. I figured that given the esoteric nature of some of these materials, it would be best to choose the a familiar videogame, one whose importance and quality everyone would be able to acknowledge immediately:

What is E.T. for Atari VCS? There are many ways to answer.

|

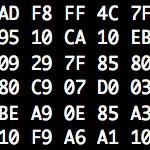

E.T. is 8 kilobytes of 6502 opcodes and operands, which you can see in a hex dump of the ROM itself [in the presentation, I listed the full hex dump on-screen]. Each value corresponds with a processor operation, some of which also take operands. For example hex $69 is the opcode for adding a value. |

|

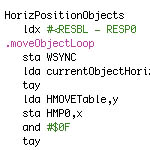

An assembled ROM is really just a reformatted version of the game’s assembly code, and E.T. is also its source code, a series of human-legible (or slightly more human legible, anyway) mnemonics for the machine op codes that run the game. |

|

E.T. is a flow of RF modulations that result from user input and program flow altering the data in memory-mapped registers on a custom graphics and sound chip called the TIA, which it in turn transformed into radio frequencies, which operates in conjunction with the television’s electron beam and speakers. |

|

E.T. is a mask ROM, an integrated circuit, on which memory (in this case 8k worth) is hardwired into an etched wafer. The photomask for a ROM of this sort was high in cost to setup, but had the benefit of being very cheap to manufacture in quantity, manufacturing in quantity certainly being one of the main features of E.T. the videogame. |

|

E.T. is a molded plastic cartridge held together with a screw, an adhesive label stuck upon it, emblazoned in turn with an offset printed label. |

|

E.T. is a consumer good, a product packaged in a box and sold at retail with a printed manual and packing cardboard, hung on a hook or placed on a shelf. |

|

E.T. is a system of rules or mechanics that produce a certain experience, one that corresponds in some ways to a story about a fictional alien botanist stranded on Earth by the name of E.T., whom a group of children attempt to protect from the xenophobic curiosity of governmental and scientific violence. |

|

E.T. is an experience players can partake of individually or together, for example as a family gathered around the television. |

|

E.T. is a unit of intellectual property that can be owned, protected, licensed, sold, and violated. |

|

E.T. is a collectible, an out of print or “scarce” object that can be bartered or displayed. |

|

E.T. is a sign that depicts the circumstances surrounding the crash of 1983. In this sense, the sign “E.T.” is not just a fictional alien botanist, but a notion of extreme failure, of “the worst game of all time”: the famed dump of games in the Alamogordo landfill, the complex culture of greed and design constraint that led to it, the oversimplified scapegoating process that ensued thereafter—otherwise put, “E.T.” is Atari’s “Waterloo”. |

All of these units of being exist simultaneously with, yet independently from one another. There is no one “real” E.T., be it the structure, characterization, and events of a narrative, nor the code that produces it, nor anything in between. Latour calls it irreduction: “nothing can be reduced to anything else,” even if certain aspects of a thing could be considered transformative upon something else.

[Indeed, there is work that looks at games from the perspective of many of these perpectives, e.g. TL Taylor on Everquest, Seth Giddings on technoculture , Bart Simon on Wii, among others. My interest in this talk was in making ontological claims rather than a social/political ones, something whose further clarification will require a break from actor-network theory. More on that can be found in my 2008 Philosophy of Computer Games keynote, and more is to come in my forthcoming (November 2009) SLSA keynote.]

Latour handles the processes of transformation through the concept of a network, comprised of actors (which can be human or non-human) behaving upon one another, entering and exiting relation. My concept of the unit operation offers another model, a unit being comprised of a set of other units (again human or non-human), irrespective of scale, comprised by a gesture similar to Alain Badiou’s count-as-one. The unit operation differs from Latourian networks and actants in important ways, but I’ll have to leave that clarification for another day.

All together, these moves allows us to steer between the Scylla of correlationism, a common problem with media studies and social scientific analyses of games, and the Charybdis of reductionism, one of the common critiques of formal and material analyses of games. Let’s consider two brief examples.

With respect to correlationism, yesterday we heard Graeme Kirkpatrick argue that games cannot partake of meaning, because their very structure works against it [this took place in a panel on aesthetics the day before]. Likewise, just before I left for the conference game designer Frank Lantz published his argument that a game is not a statement. Such ideas reject claims some have made, including myself, about games’ ability to do construct meaning and to make arguments. Yet the beauty of a flat ontology is that we need not hold that games can only mean, and Graeme, Frank, and I can continue to get along like mimes and urologists at the disco.

With respect to reductionism, when Jesper Juul fell upon the disassembled program ROM for the Pac-Man coin-op a year ago, he posed the question, “Is this what Pac-Man really is?” The answer is yes, in one sense. The code that is Pac-Man very much really is. But then no, in another sense, it is not all that is when it comes to things Pac-Man.

Likewise E.T. is never only one of the things just mentioned, nor is it only a collection of all of these things. Paradoxically, a flattened ontology allows it to be both and neither. We can distinguish the ontological status of game-as-code from game-as-play-session without making appeal to some higher-order notion of game as form, type or transcendental. To make earnest a term used in jest by Levi Bryant, this is a slutty ontology, one in which anything is thing enough to have a good time.

Similarly, one way of reading the critique of correlationism is not as a rejection of correlations, but as a rejection of only one correlation (for Meillassoux, being-for-thought; for Harman, being-for-humans), and an embrace of multiple correlations, as many as we’d like or need. This is certainly the position Harman takes when he claims that the human/world relation is just a special case of the relation between any two entities. If we take the lure of slutty ontology seriously, we might foresee a new era of ontological copulationism.

Such a perspective invites a surprising truth: game studies means not just studies about games-for-players, or as rules-for-games, but also as computers-for-rules, or as operational logics-for computers, or as silicon wafer-for-cartridge casing, or as register-for-instruction, or as radio frequencies-for-electron gun. And game is game not just for humans but also for processor, for plastic cartridge casing, for cartridge bus, for consumer, for meme carrier, and so on. This is an entirely unexplored area, and a direction I’ve become most interested in exploring.

One last thing: what could we call this clutter of thingness that replaces our previous, overly simplified, hierarchical and correlationist answers to the question, “what is a game?”

Even though I want to resist Latour’s notion that being only exists through relation, as well as his related notion of the network, which I consider overly normalized, we might instead adopt his concept of the imbroglio, a confusion in which “it’s never clear who and what is acting” (Reassembling the Social, p. 46). Latour’s original example of the imbroglio is related to human knowledge, such as the way reading a newspaper involves us in a tangle of different fields and areas, connected but hybridized. Here’s Latour:

hybrid [newspaper] articles sketch out imbroglios of science, politics, economy, law, religion, technology, fiction. … All of culture and all of nature get churned up again every day, … yet no one seems to find this troubling. (We Have Never Been Modern, p. 2)

But Latour’s imbroglio feels too formal, too organized for my taste. An imbroglio is an intellectual kind of predicament, a muddle to be sure, but a muddle wearing an ascot.

Perhaps we could adopt actor-network theorist John Law’s account instead. Law tells a story about a research project he conducted with a collaborator, in which the two investigated the way a hospital trust handled patients with alcohol-caused liver diseases. As in many bureaucratic situations, they quickly discovered considerable logistical complexity. In some cases, but not others, patients from a city-central advice center were advised to go to treatment programs, but they’d have to make an appointment. Yet, many in the hospital didn’t have the same perception of the advice center, considering it a location for drop-in treatment. The situation was, Law concluded pragmatically, a “mess.”

Law reflects on the concept of mess as a methodological concern, one that resists creating neat little piles of coherent analysis. Instead, it is necessary to pursue “non-coherence.” Says Law, “This is the problem of talking about ‘mess’: it is a put-down used by those who are obsessed with making things tidy. My preference, rather, is to relax the border controls, allow the non-coherences to make themselves manifest. Or rather, it is to start to think about ways in which we might go about this.”

Note the difference between Law’s mess and the formalism of structuralist approaches: it is not some overarching system operation that accounts for all things, a set of cultural morés or a set of regulations for a particularly well-scheduled orgy to be held on glossy birch flooring, but a loose-and-fast structuring of units-for-whatever, not just for the human actors implicated in events.

A mess is not a pile, which is neatly organized even if situated in an inconvenient place underfoot. A mess is not an elegant thing of a higher order. It is not an intellectual project to be evaluated and risk-managed by waistcoat-clad underwriters. A mess is a strew of inconvenient and sometimes repellent things. It is less an imbroglio of the sort one finds in a painting of Pollock or Picasso, and more the mess one finds in a sculpture of Keinholz. A mess is an accident. A mess is a thing that you find where you don’t want it. A mess is the cascade of broken glass on the floor when you miss the alarm clock and catch the water glass. A mess is the heap of hot, unseen dog shit on the stoop, and then on the stoop and the bootsole. A mess is inelegant, a clutter, a shamble, a terror. We recoil at it, yet there it is, and we must deal with it.

Videogames are a mess. A mess we don’t need to keep trying to clean up, if it were even possible to do so.