One of my gripes with Henry Jenkins’s book Convergence Culture was its tendency to privilege pop cultural fan activity to other sorts of attention. Appealing though they may be, I wondered if Harry Potter and Survivor really sat at the pinnacle of human creativity in the way that the book implied. One of the problems that concerned me was the way fan activity can act as a type of free labor for the owners of media properties. Jenkins has since responded to this objection in numerous ways, including on his blog and during his keynote presentation at the Serious Games Summit DC 2006.

But there is an alternative I hadn’t considered seriously before, a variant of fandom that Jenkins also doesn’t discuss in his book: fan products sometimes take advantage of missed commercial opportunities on the part of property owners.

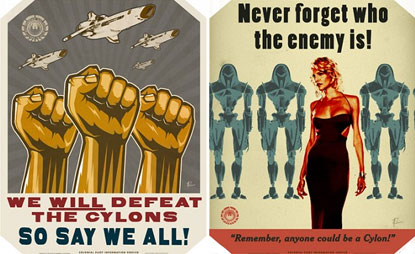

To be sure, licensed products and accessories have taken a turn for the crafty more and more in recent years. Take Quantum Mechanix, for example, who has produced gorgeous, officially licensed posters based on sci-fi standbys Battlestar Galactica and Firefly, among others. Artisinal despite their mass production, Quantum Mechanix’s posters feel authentically amateur thanks to their attention to arcane detail.

But other vendors have managed to exploit a similar sense of authenticity by slipping under the radar of official licensing. The t-shirts of Glarkware are perfect examples. These limited-edition, screen-printed shirts each fixate on a recognizable icon from contemporary pop culture, never naming it directly to avoid infringement. The results are usually clever and subtle: Toaster (Battlestar Galactica); Capitoline Brotherhood of Millers (Rome); Office Manager (Mad Men); Ask Me About Harry’s Code (Dexter); Stapler (The Office).

What makes Glarkware’s designs appealing is not only how deftly they capture specific aspects of fictional worlds created in mass media, but also that the owners of the properties they riff didn’t bother to seize the opportunity. Other, similar examples can be found on craft trade site etsy.com, where just about any pop cultural reference can be found in knit, letterpress, or canvas.

This is a type of production that sits between a celebratory and critical treatment of media. These creators both endorse and exploit the media properties they admire: the endorsement comes via the revelatory, clever, and detailed attention they pay to specific aspects of a film or television show, the exploitation from commercializing it in a way its producers couldn’t imagine.

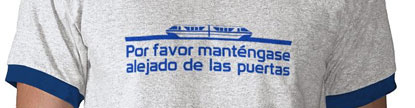

This year I attempted my own fan exploitation, one that has been modestly successful. Anyone who visits Disney World and rides the monorail hears the friendly announcer ask riders to “please stand clear of the doors,” once in English and then again in Spanish: “por favor manténgase alejado de las puertas.” Like the repetitious emotes of real train transit systems (the London tube’s “Mind the gap” or the New York subway’s “Please stand clear of the closing doors”), this line becomes cultural texture. As I’ve noted before, the monorail serves as an attraction unto itself, a Transportland for a middle America that doesn’t experience rail transit as a part of everyday life; it’s a kind of transportainment. Furthermore, the Spanish language announcement functions as a type of Orientalism, making the ordinary feel strange and exotic for those who aren’t used to non-English languages. For all these reasons, the announcement becomes a notable and memorable part of a Disney vacation.

But Disney itself has done little to commercialize the opportunity. At times they sell a single t-shirt with the phrase, in Spanish, accompanying a forgettable graphic of the monorail itself. As far as I can tell, such shirts are available only in the Disney Contemporary Resort giftshop.

I made two designs, one a 1960s vintage Fantasyland interpretation of both monorail and typography, the other an accurate depiction of 1982 EPCOT typography (in dark and light), and I put them up on print-on-demand service Zazzle. The results have been quite positive; not only am I happy with the designs and the print quality, not only did they allow me to print custom shirts for our own trip to Disney World, but also they actually sell pretty well.

What name do we give this simultaneous exploitation and celebration of highly corporatized, mass media entertainment? It’s not at all like culture jamming, nor is it like fandom of the sort that Jenkins advocates. It’s a kind of fandom that knows it is sticking it to the very man to whom it also pays homage. And furthermore, it is not just fandom for fandom’s sake; rather, it is fandom for surreptitious profit. This is not a traditional license, nor is it a relationship of symbiosis.

Here’s one idea. A license is a grant of permission from an authority to do or use something. We get a license to drive, for example, or to trade, or to carry a gun. A license to use a media property is typically sold with limitations for use, often separately by medium (for toys, for videogames, for apparel, and so forth). But licenses also demand accountability and enforcement. A boy too young to drive a car might nevertheless drive a truck or tractor on a farm or ranch, since nobody would be around to enforce the license. Or better put, those in authority would have little knowledge that violation was taking place. Such license violations allow themselves by falling off the radar of authority. They are noise. Enforcement would be logistically difficult, perhaps impossible. This is the stuff that slips through the cracks of enforcement because it is waste, detritus.

To be sure, detritus that proves particularly valuable might elicit recovery by property owners, but doing so requires slogging through the slop to find it. And with all the volume on the Internet, that’s a lot of dregs through which to dig.

Comments

TClark

Here on the west coast, it’s the spanish reminder to remain seated at the end of the Matterhorn:

“Remain seated please. Permanecer sentados, por favor.”

I’d buy a matterhorn “permanecer sentados” shirt.

———-

But this whole thing isn’t really all that new. When I was a kid and you shopped at the cut-rate store that sold shoes and shirts with suggestive-but-not-infringing Space Characters, my peer group called them called wannabe clothes.

The Go-bots were wannabe Transformers, BSG was wannabe Star Wars, and Trips were wannabe Zips.

Ian Bogost

Tim, good point about the Matterhorn. Since it doesn’t appear at Disney World, it’s been some years since I’ve encountered that announcement. It might be time to crank out another t-shirt.

I hear what you’re saying about Transformers and Gobots and the like, but I think that’s different. Those are exploitations, to be sure, but they are massively industrial corporate exploitations of pop cultural trends, not individually crafted homages-for-profit like I’m interested in here. Yes?

TClark

Yes, I can see the distinction, from a social/cultural standpoint between corporate exploitation and the more personal instances you describe. Probably that the former is merely crass but the second one has both an exploitative/appreciative feel. Perhaps what you’re describing is a little more like the genre exploitation/love-letter Tarantino films.

jccalhoun

I’m not sure that a clear division can be made between an individually made “poaching” of mass media and a corporate made bootleg. Cafe Press is basically build on these kinds of things (and Zazzle and other Cafe Press competitors) but what are those companies if not massively industrial corporate exploitations of individual needs to express ourselves?

And moreover, if we go beyond knockoff Transformers and toys to things like Black Bart Simpson shirts it seems that these are probably made by entrepreneurial individuals rather than real companies.

It also seems like the unauthorized images of Calvin (of Calvin and Hobbes) peeing on something that are seemingly ubiquitous here in the midwest are also an example of this phenomenon. Watterson has refused to license Calvin even though there is a consumer demand for them and the gray market has attempted to fulfill that desire. (Although it may be that the people who buy these aren’t buying them because of Calvin but rather some dislike of the thing being peed on and very well have no idea who Calvin is)

Ian Bogost

The Calvin appliqués are a great example, I agree. Same with the Black Bart shirts.

But Zazzle and Cafe Press as companies operate on a different register from the individuals who use those services to exploit media properties in the way I am describing. There is no doubt that such services have accelerated the practice, and I empathize somewhat with the notion that those companies’ relationships to individual creators is exploitative. Perhaps it is. But it still seems more symbiotic than Glarkware’s relationship to Mad Men, or mine to the Disney monorail.

Ian Bogost

Please Stand Clear of the Closing Rights

How Disney and Zazzle conspire against me (and you)